Why Unhealthy Relationships Can Be So Hard to Leave

It’s easy to see a relationship is no longer working, yet acting on that insight can feel impossible. This article explains why fear, instability and old rules stall movement — and why building steadiness, instead of forcing a decision, brings the situation into focus.

Relationships ➞ Relationship Dynamics & Patterns

Relationship problems are often easy to recognise once they have taken shape: widening differences in priorities, mounting friction caused by diverging expectations, and the realisation that the partnership no longer aligns with the direction you want your life to take. If these dynamics remain unresolved, you may start weighing up whether the relationship is still viable.

The dilemma intensifies the moment you imagine ending it. Even the notion can trigger a tight, intrusive surge of fear, interrupting clear thinking. This tension arises from the contrast between familiar discomfort and the uncertainty of a future you cannot yet picture. Shared routines and responsibilities come into sharper focus because they represent the structure of your daily life, and that structure still holds value even when the relationship itself feels strained. Rational clarity and emotional readiness move at different speeds, and that internal split limits movement even when the facts seem obvious.

The Split Between Knowing and Staying

It is reasonable to assume that recognising a relationship as harmful would lead to leaving. This assumption misses the internal bind that usually emerges. Clarity and action sit far apart, not for lack of insight, but because your system evaluates change through a different lens. The response is driven less by what you know and more by whether you feel stable enough to cope with the disruption that would follow.

Your reflective mind registers the current strain. Your emotional brain registers the potential loss of predictability and treats this as instability. When these two appraisals diverge, taking action becomes harder.

Why Rational Clarity and Emotional Readiness Don’t Align

Rational clarity relies on what you can see and name directly. You can list the arguments for leaving a relationship and see the unstable patterns, the volatility and the cumulative toll on your wellbeing. Yet emotional readiness rests on something different: perceived stability. It asks whether you feel stable enough to absorb the disruption that separation would bring.

When the emotional system senses instability, preservation receives priority over change. Logical conclusions lose influence not because they are wrong, but because they demand a shift that your system may not yet feel able to withstand. This is why even small movements toward a decision can lead to hesitation or a return to what is familiar, despite its limitations.These responses are attempts to regulate, not indicators of uncertainty about what you see.

Emma's Story

Emma, 39, has two children and a demanding job. The erosion was gradual, almost unremarkable at first. Her partner became noticeably less engaged in shared aspects of their life. Disagreements took on a sharper edge. Minor criticisms, once voiced gently, were now expressed with a harder tone. Weekends became exercises in keeping the peace. While there was no one single explosive event, the cumulative effect was draining.

She noticed his withdrawal in the way conversations tightened and small exchanges became brief. But each time she considered raising her concerns, daily life intervened: the school run, dinner, bedtime, bills. Her own needs were pushed to the background, and the practical demands left little space to reflect on what was changing and how to respond.

Brief periods of calm created just enough relief to suggest things might settle. She felt uneasy but told herself it was only a phase. The thought of leaving felt impossible, not because she believed the relationship was working, but because she could not see how she would manage the fallout while already stretched thin.

How Familiarity Becomes “Safety”

The nervous system learns through repeated patterns. When a relationship develops predictable cycles, including those marked by tension or withdrawal, your system adapts to those cycles. You begin to recognise which responses reduce tension and which behaviours maintain peace. Over time, this predictability may feel steadier than the uncertainty of change. Familiar discomfort can feel more workable than a future you cannot yet picture.

“I’m Unhappy but Scared to Leave”

The fear here is not abstract. Each concern points to an aspect within your life that would feel exposed if the relationship ended: emotional familiarity, daily order, your sense of yourself as a partnered person, social belonging and the risk of making a choice you later question or regret. These are not arguments to stay. They show the aspects of stability your system is trying to preserve. When these concerns go unexamined, the relationship can feel like the only place where those needs are held, even if the fit is strained.

The End of History Illusion: Why the Future Feels Fixed

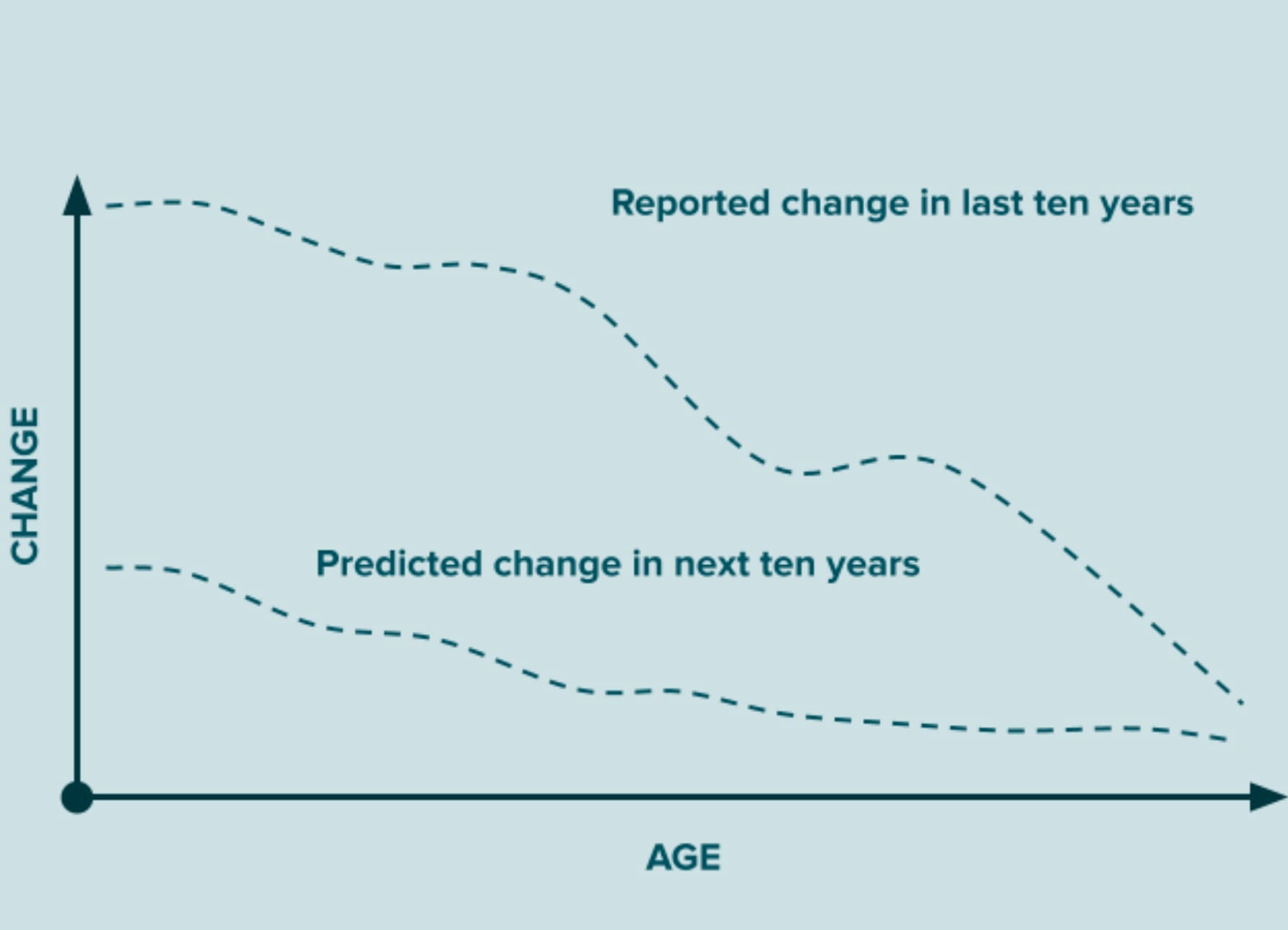

A further force can hold you in an unhealthy relationship: a bias known as the “end of history illusion”. It describes the tendency to recognise how much you have changed in the past while assuming far less change will occur in the future.

You can look back and see earlier versions of yourself with clarity. But when you project forward, the mind provides only vague sketches rather than a clear sense of who you might become. The past is fixed in memory. The future is ambiguous, so the mind defaults to continuity and treats your current state as a stable reference point.

This bias shapes relationship decisions by exaggerating the permanence of present emotions. Loneliness, uncertainty or vulnerability in the months after a separation are imagined as enduring traits rather than temporary conditions. The mind mistakes immediate feelings for indicators of who you are, not passing responses to a difficult period.

This is not optimism or pessimism. It is a cognitive bias. Recognising it interrupts the belief that your current capacity defines your future capacity. Your history shows that you have changed before in ways you couldn’t have predicted, and that process hasn’t stopped.

Why Am I Staying When I Know It’s Unhealthy? Early Rules and Old Fears

Present-day decisions often draw on established emotional habits. Many people grow up learning that stability depends on being accommodating, undemanding or conflict-averse. Approval and calm tended to come when they minimised their own impact. Tension reduces when they soften their needs. Over time, these strategies settle into implicit rules for maintaining safety.

These rules often show up as quiet convictions:

Leaving means I failed.

My needs will create friction.

It’s my responsibility to keep things on an even keel.

When these internal rules surface, leaving does not feel like a decision. It feels like violating a pattern that once ensured acceptance. The pull to stay is not loyalty to the present relationship but fidelity to an older template for remaining safe.

This is not pathology. It is continuity. Your system relies on strategies that once worked, even when the current context no longer requires them.

The Cost of Forcing a Decision Too Soon

When fear rises, people try to steady themselves by pushing for a decision: I have to leave now, or I have to make this work. Urgency increases as a response to feeling out of control. It offers a momentary sense of direction, but decisions made in emotional turbulence rarely hold. They slide back to hesitation because the underlying instability remains unchanged.

Acting before you have a more settled mind does not shorten the process; it extends the period of uncertainty. The aim is not to rush toward a conclusion. The work is to build enough internal stability so that, whichever direction you take, your decision rests on clearer judgment rather than a reaction to fear.

What Fear Is Actually Pointing To

Fear highlights what feels exposed. It marks the areas where you doubt your capacity to cope: emotional load, practical disruption, identity shifts or long-standing rules about responsibility. Fear shows what you believe you cannot yet manage, not what is beyond your reach.

Useful questions include:

What exactly am I afraid will happen if I leave?

What am I afraid will happen if I stay?

Which concerns belong to the present, and which echo older patterns?

Putting these answers into words externalises them. Held in the mind, fears blur together. Written down, they take shape and become something you can assess rather than react to.

Working With Fear Before You Decide

Internal stability develops through small, deliberate steps. Sorting your fears into practical, emotional and social categories helps you see which concerns relate to concrete problems and which arise from older expectations or habits.

Strengthen the practical ground first: finances, housing, childcare, routines. A clearer logistical base reduces the sense of instability.

Inside the relationship, notice the small moments when you hold back or give in, and pay attention to how you respond. These moments reveal where tension rises and where old patterns begin to guide you.

Seek perspective from someone outside the dynamic. External distance makes relational patterns easier to see.

You do not need to resolve the future of the relationship to begin stabilising yourself. Stabilisation is part of the assessment, not the outcome.

Should I Stay or Should I Go: A Clear-Eyed Way Forward

The task is not to force a decision. The task is to reduce the fear that distorts your reading of the situation. When fear settles, your thinking becomes steadier and the situation becomes easier to interpret.

From steadiness, two directions become clearer:

• staying for a period while strengthening boundaries and communicating with more precision

• preparing to leave with attention to your wellbeing and any shared responsibilities

Neither path requires haste. Both require clarity. Movement becomes possible when your choice reflects understanding rather than an attempt to escape discomfort.

A Quiet Example of Movement

Daniel had been weighing the end of his relationship for several months. Each attempt to face what he was feeling increased his unease. He worried about hurting his partner. He feared facing life alone. He fretted about making a choice he might later regret.

Rather than forcing an answer, Daniel began to organise himself. He wrote down the pressures pulling on him and separated the practical issues from the emotional ones. He rebuilt basic routines that helped him stay anchored. He slept consistently, walked every day, and sought interaction with people outside the relationship dynamic.

The tension remained, but it no longer dictated Daniel’s next move. He could tell which concerns belonged to the present and which came from older patterns. The decision to leave was made without pressure. Daniel ended the relationship with care. He recognised the loss and acknowledged that he now had enough internal footing to manage what followed.

What matters is that the decision came from clearer judgment rather than fear. The process is still ongoing, but it now unfolds from a calmer internal state rather than urgency. The work is to build enough internal footing so fear no longer shapes your next move.